Place Card

Prisca Mbonu, Class of 2026

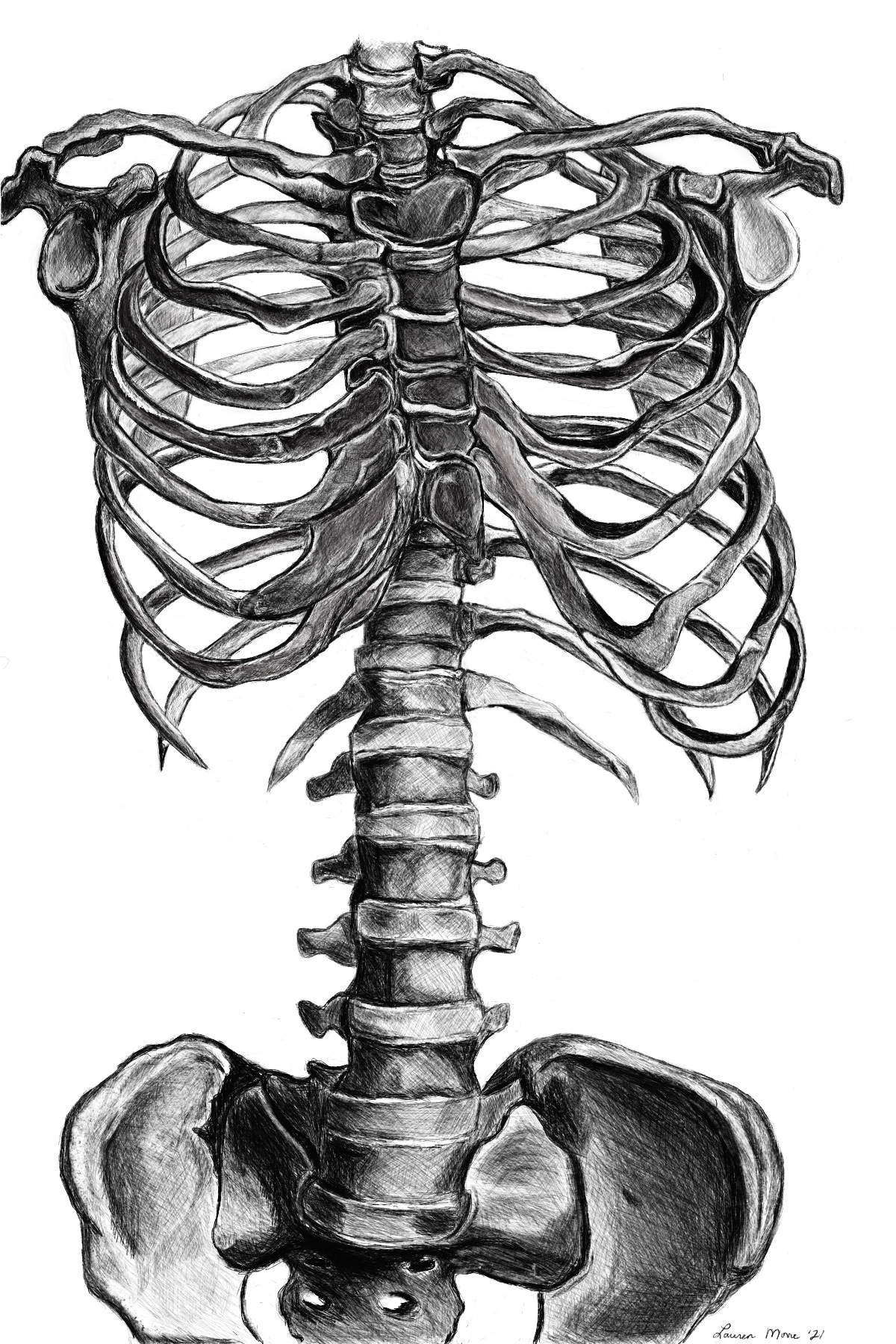

The first step into the Cold cadaveric laboratory The first whiff of formaldehyde That seems to permeate the walls The first moment when the shiny...

Read MoreWelcome to HuMed, a hub to engage in innovative, multidisciplinary practices in medical humanities. Along with faculty-led workshops, HuMed will welcome guest artists from around the country to share their knowledge and best practices in the field of humanities in medicine. The HuMed journal is a medical humanities and creative non-fiction online publication featuring thematic writing, along with other forms of humanities-based contributions from students, faculty, and staff.

Prisca Mbonu, Class of 2026

The first step into the Cold cadaveric laboratory The first whiff of formaldehyde That seems to permeate the walls The first moment when the shiny...

Read More

Prisca Mbonu, Class of 2026

The first step into the

Cold cadaveric laboratory

The first whiff of formaldehyde

That seems to permeate the walls

The first moment when the shiny zipper is pulled

To reveal what is hidden beneath

The first cut through skin

Into fat, fascia, and finally, muscle

The first surge of guilt

At the sacrifice of another

The first feeling of gratitude

Towards a complete stranger

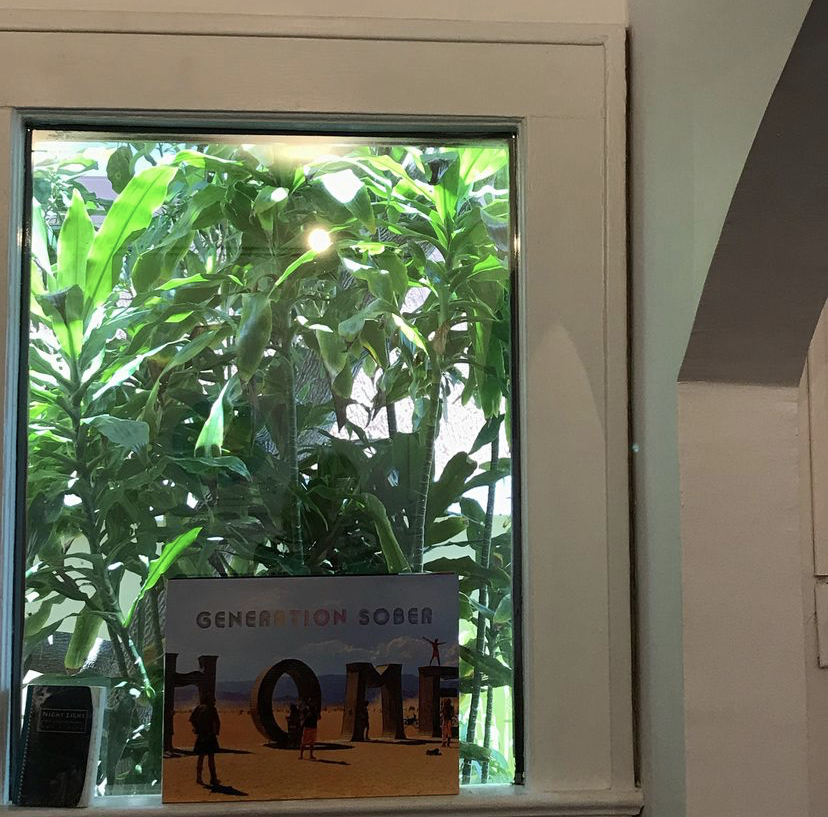

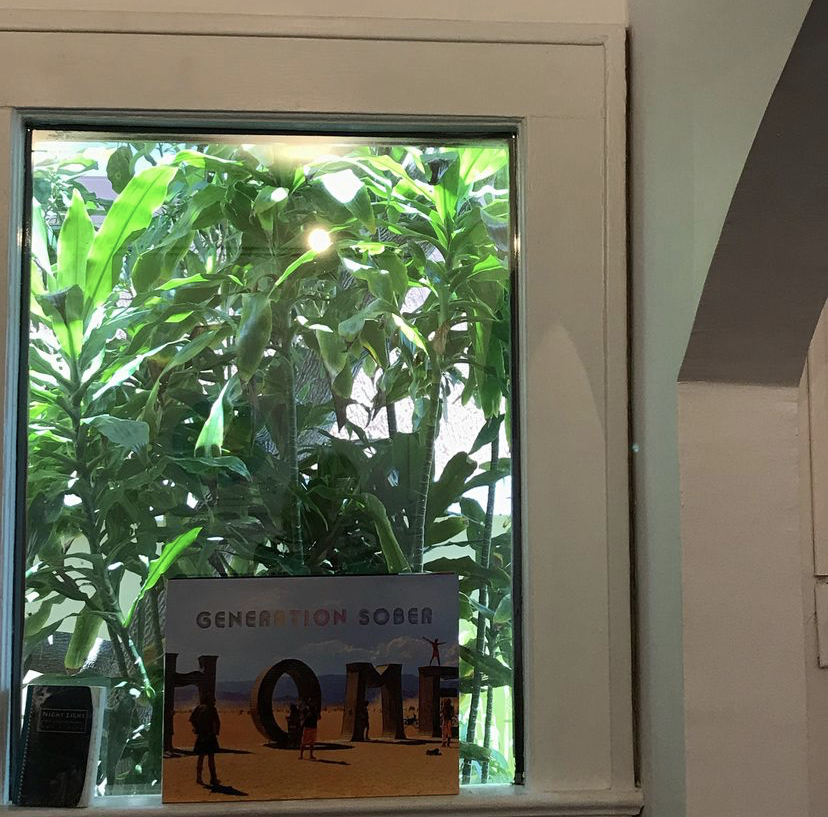

There lies a place card

Mounted against a rusting metallic stand

With words printed on a purple, laminated sheet

They tell me what is left of you

Age. Sex. Cause of death.

But your body tells an even greater story

Of pain, surgical scars

Of adventures, tattoos

Of joy, laugh lines

Of hard work, calluses

Of life, childbirth

In you, I see a collection of firsts too

Ngoc Bao Nhi “Mariana” Nguyen, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint): Iron Deficiency Anemia: Iron is essential in making hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells. Iron deficiency anemia...

Read More

Ngoc Bao Nhi “Mariana” Nguyen, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint):

Iron Deficiency Anemia: Iron is essential in making hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells. Iron deficiency anemia is a condition in which blood lacks adequate healthy red blood cells due to low level of iron. Common symptoms include fatigue, irregular heartbeat, pale or yellowish skin, and cold hands.

Part B (Poem):

I lack red blood cells

Lightheaded, sometimes I get

I need grass-fed beef.

Ngoc Bao Nhi “Mariana” Nguyen, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint): Iron Deficiency Anemia: Iron is essential in making hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells. Iron deficiency anemia...

Read More

Ngoc Bao Nhi “Mariana” Nguyen, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint):

Iron Deficiency Anemia: Iron is essential in making hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells. Iron deficiency anemia is a condition in which blood lacks adequate healthy red blood cells due to low level of iron. Common symptoms include fatigue, irregular heartbeat, pale or yellowish skin, and cold hands.

Part B (Poem):

When the iron is running low,

A shadow of fatigue begins to grow.

Pale echoes in each step I take,

Anemia’s weight, a heavy ache.

In veins, a river without its might,

Transferrin, the captain, lost in the night.

Cells, like soldiers, weary and dried,

Battling fatigue, a crimson tide.

When the iron is running low,

Hematocrit staggers below.

Heart’s rhythm stumbles in faltering beat,

A symphony of exhaustion, a silent defeat.

Blood cells fade in ghostly wail,

In the mirror, my complexion pale.

Cold fingertips where blood don’t flow,

When the iron is running low.

A labored sigh in every breath,

Iron’s death, my own Macbeth.

The world spins, a dizzying show,

When the iron is running low.

Iron returns in distant dreams,

In languor’s grip, a silent scream.

Yet hope lingers like a resilient ember,

For iron’s return, a strength to remember.

Ngoc Bao Nhi “Mariana” Nguyen, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint): A cold is a common viral infection of the nose and throat. Symptoms include runny nose, sneezing, and...

Read More

Ngoc Bao Nhi “Mariana” Nguyen, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint):

A cold is a common viral infection of the nose and throat. Symptoms include runny nose, sneezing, and congestion. Because antibiotics only fight bacteria, and not viruses, they’re usually ineffective against colds. The condition is usually harmless and mostly resolves on its own within two weeks.

Part B (Poem):

With sniffles and sneezes, he caught a cold,

In bed he rested, his sinus consoled.

No pills would he take,

Just warm tea with cake,

A viral invasion, not bacteria, behold!

Naimah Sarwar, Class of 2025

And he beams, I’m golden, just golden. I’m golden and also, what exactly is a seizure? You see, he’s been drinking that Golden liquid, his...

Read More

Naimah Sarwar, Class of 2025

And he beams,

I’m golden, just golden.

I’m golden and also,

what exactly is a seizure?

You see, he’s been drinking that

Golden liquid, his golden ticket

home. His ticket back to

his golden days, a golden daze.

That heart of gold irradiating

his skin.

Will you think about quitting?

A crescent moon, ear to ear.

I’m golden,

everything is golden.

Golden boy

his eyes, all that glitter.

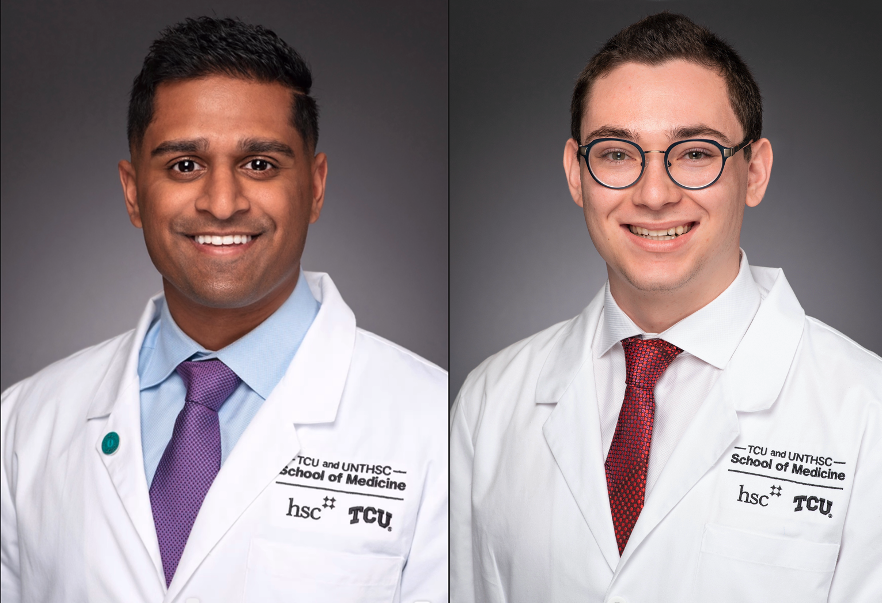

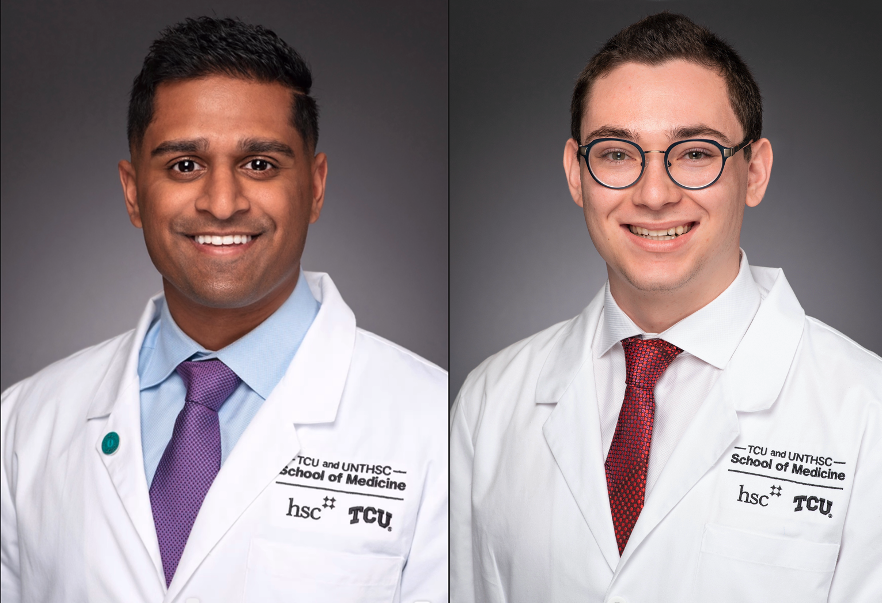

Jayesh Sharma, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint): Migraine with aura is a type of migraine headache characterized by the presence of sensory disturbances, known as...

Read More

Jayesh Sharma, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint):

Migraine with aura is a type of migraine headache characterized by the presence of sensory disturbances, known as an “aura,” preceding or accompanying the headache. The aura typically involves temporary, reversible visual, sensory, or language disturbances that develop gradually over several minutes and usually last for less than an hour.

Part B (Poem):

My eyes open to stark cacophony

Sharpened colors,

Cutting me with their keen vibrancy

Jagged sounds,

As if hitched breaths

Hiding from nearby pursuit

I blink rapidly

Trying to find my place;

A lone straggler

Moored on a lost island

A cloud passes

Rolling past brief farewells

Frosted pearls

Flooding into a conductor’s crescendo

A neighbor glances

Assuming narcissistic attention

Brief windows opening

Caught under heavy fantasy

A babe wails

Fighting confusion with volume

A solo instrument

Caught between fractured arpeggio

I try to stay afloat

flailing with a fool’s futility

Assuming survival

to be adequate reprieve

These blurred lines adjust

as grief tends to do

Moving from pounding beats

unto dull aches

Dragging marionette limbs

Into rehearsed movement

The moment passes

Or perhaps I tell myself it does

Swaying to faint decrescendo

Distraction replacing reality

An easy pivot,

One I have grown accustomed to

Both eyes close once more

Doorways bleeding light

from what they hide behind;

A hopeful illumination

A slight knocking,

as if not to startle beauty awake

I relish my brief ignorance

Into the dread of inevitable beginning

as if sensing a conductor’s crescendo

Building up into a familiar movement

Slowly,

Towards stark cacophony

Jayesh Sharma, Class of 2027

My father bought a ping pong table. It's nothing special. Two sides of green space separated by a thin, rectangular net. Blue and red-halved paddles,...

Read More

Jayesh Sharma, Class of 2027

My father bought a ping pong table.

It’s nothing special. Two sides of green space separated by a thin, rectangular net. Blue and red-halved paddles, built to accentuate each “tick” and “tock” between opposing sides.

He always asks me when I want to play. It’s as if he wants to justify the hassle of getting this table by using it as much as we can. He was the same about his pizza maker, camera, and lawnmower. He’s a dad in normal ways like that, finding color to tint dull days.

Playing with him is quiet.

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Ti- ah, close.”

At times, between hits, a conversation will ripple between us. It’ll be something small; maybe mom’s latest gripes, Shruti’s upcoming dance performance, or pieces of wisdom he likes to impart.”

Mostly though, it’s quiet.

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Ti- ah, I’ll get it.”

It’s a steady beat, one I feel my thoughts playing cadence to. It’s calming, letting me flow as my paddle does.

He spent the first five minutes of our time today adjusting things in our garage. He then felt finicky about how centered the table was, and then about how many balls he could hold. Growing up, these tendencies of his would’ve annoyed me to no end; I would’ve felt that he was wasting time while I just wanted to play. That old feeling hinted upwards still, but now I see things a bit more from his perspective. I realize that he was expressing how he wanted our time together to go smoothly, adjusting small things as his way to protect our time.

I haven’t always liked my dad. I used to feel he was the epitome of who I didn’t want to be. I would then feel frustrated that I still admired him for his intellect and work ethic. We used to argue a lot, especially after my sister was born. Everything, from my independence to his anger, was constantly put on the table with no reprieve. Small times like these, ones where we can quietly enjoy each other’s company across the table, show how far we have come.

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Tick.”

“To-I have another one, leave it.”

I haven’t always been the best son. But he’s been okay with that. In spaces where our conversations ripple, he’s understood the storm which has come before. We’ve both had irrational times with each other, but we always knew that we would always be in each other’s lives. Sometimes, that fact annoyed me more than anything else.

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Tick.”

“To- there we go. Last one?”

“Sure, I’m losing breath anyways.”

Two sides of green space separated by a thin, rectangular net. Blue and red-halved paddles, built to accentuate each “tick” and “tock” between opposing sides. That’s how I used to feel with him. Growing up has allowed me to see that it isn’t that way. At some point, we put down the paddles and walked away together. The ripples calmed, the storm passing.

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Tick.”

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

“Tick. I technically cheated on the last one.”

“Tock.”

“Tick. Ah well, who’s keeping score anyways.”

“Tock.”

“Tick.”

“Tock.”

…

“Want to play again tomorrow?”

“Sure dad.”

Prisca Mbonu, Class of 2026

We entered the procedure room to find the final patient of the day, Ms. K, sitting upright on the examination table. She had already changed...

Read More

Prisca Mbonu, Class of 2026

We entered the procedure room to find the final patient of the day, Ms. K, sitting upright on the examination table. She had already changed out of her own clothes and into the customary light blue patient gown, with a white sheet draped over her legs. Her manicured hands were clasped together, fingers wringing with uncertainty. “Hello, Ms. K,” my preceptor, Dr. L, greeted. “I have a medical student with me today. Are you comfortable with her observing your procedure?” Ms. K’s gaze shifted towards me, and after a moment of hesitation, she nodded slowly and said, “Sure. The more the merrier, I guess.” After thanking her, I gave my introduction, a routine practiced countless times during my two years of training.

My preceptor handed Ms. K two consent forms which clearly stated the risks and benefits of the procedure. I watched as Ms. K’s barely audible sighs accompanied the turn of each page as she read before eventually signing her consent. Soon after, we were joined by two nurses, bringing the room’s occupancy to a total of five. The procedure we were preparing to perform was an endometrial biopsy. Ms. K, a 58-year-old woman, had been experiencing postmenopausal vaginal bleeding for some time. In such cases, an endometrial biopsy is often an initial test for evaluation.

The procedure involves inserting a device into the uterus to collect samples to help determine the source of bleeding. Understandably, patients often find this procedure to be unpleasant and painful, which contributes to heightened levels of anxiety. Furthermore, the potential outcomes of the procedure only serve to worsen this anxiety. This wasn’t Ms. K’s first experience with the biopsy; she recounted her previous ordeal where inconclusive results left her disheartened and without answers. I understood her frustration at the entire situation, her escalating worry about her troubling symptoms, and her desperate need to finally have a diagnosis.

So did Dr. L, who gently held Ms. K’s hand and assured her that, while some discomfort was inevitable, she would do her best to minimize it. The reassurance brought a grateful, tearful nod from Ms. K, and the room’s atmosphere softened. The rest of us chimed in with words of encouragement, and I noticed Ms. K starting to feel more at ease. “Ok. I’m ready,” Ms. K said with a weak smile. While one nurse assisted Ms. K into the lithotomy position, the other organized the required instruments on a stainless steel tray. As the nurse explained the functions of the speculum, tenaculum forceps, Allis clamp, uterine dilators, and suction curette for my learning, I instinctively positioned myself to block Ms. K’s view of the instruments, fearing that seeing them would amplify her anxiety.

As we prepped, we engaged Ms. K in conversation about her background. We learned that she was born in the Caribbean. She spoke wistfully of the beauty of her homeland, painting vivid pictures of breathtaking beaches adorned with rolling waves and caressed by gentle breezes. She reminisced about cerulean skies and distant horizons that beckoned her each morning. Somehow, the conversation veered into light-hearted banter about handsome men from the islands, eliciting hearty laughter from all of us.

Her nostalgia momentarily distracted her from the impending procedure, but she was brought back to the present at the insertion of the speculum to visualize her cervix. She winced, a soft whimper escaping her lips. “Would you like one of us to hold your hand? You can squeeze tight if it hurts,” Dr. L offered. “Just try not to break our medical student’s arm,” a nurse quipped, and more laughter reverberated through the room with Ms. K joining in. In that room, where tension and camaraderie were intertwined with one patient at the heart of it all, I felt a strange sense of kinship among strangers. Once again in my training, I was reminded of how connections could be found in the most unexpected places.

Throughout the procedure, we continued to offer words of encouragement and lighten the mood with jokes. Ms. K kept her eyes tightly shut, breathing shallowly through pursed lips. Occasionally, a faint smile crossed her strained features. I wondered if behind her closed eyelids, she envisioned scenes of deep blue waters and golden sands from her childhood. When the procedure concluded, I bid farewell to Ms. K and made a mental note to follow up on the biopsy results. I hoped they would provide the answers she needed and bring her the relief she deserves.

Kenneth Le, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint): Mitral stenosis is the narrowing of the mitral valve leading to reduced blood flow between the left atria...

Read More

Kenneth Le, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint):

Mitral stenosis is the narrowing of the mitral valve leading to reduced blood flow between the left atria and left ventricle. It can lead to complications such as arrhythmia, heart failure, and thromboembolism.

Part B (Poem):

Rheumatic fever

Fused to my friend, I am stuck

Snap then a rumble

Andrew Armstrong, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint): Psoriasis is a skin disorder affecting individuals with an underlying genetic predisposition who have been exposed to a...

Read More

Andrew Armstrong, Class of 2027

Part A (Brief description of chief complaint):

Psoriasis is a skin disorder affecting individuals with an underlying genetic predisposition who have been exposed to a “triggering event” such as an infection or medication. Psoriasis manifests as a red, scaly, intensely itchy rash that can occur anywhere, but are especially prevalent on the head, elbows and knees. The rash bleeds easily when picked and can even cause other symptoms like pain in the hands and back, as well as finger and toe nail disfiguration.

Part B (Poem):

I itch my arm, I don’t even realize I do it anymore

It bleeds, it usually does

I don’t realize when that happens anymore

I do realize when people stare, that’s harder to get used to

And they never stop, never

I feel like the lepers of biblical times

They were deemed unclean to live among others

I’m deemed unfit to be ignored

So I pick, I bleed, people gawk

Med students analyze

Tired residents check me off their list of “to-dos”

Attendings use me as a teaching point

But they stare too, they all do

And they never stop, never

I get jealous of the other disorders

Things like burns, broken bones, cancer even

At least people know they can’t get cancer from being around people with it

People always wonder if they can get what I have

Then I feel guilty for that thought

At least this won’t kill me

But I would give the anything for it to stop

Jesus healed the leper

If he came and healed me I wouldn’t forget to say thank you

I wonder if he’d stare too

Ope Duyile, Class of 2026

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Cysts on my ovaries? The shock of it all. Reproduction is not until the next block, I don’t know much…yet PCOS The...

Read More

Ope Duyile, Class of 2026

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome.

Cysts on my ovaries? The shock of it all.

Reproduction is not until the next block, I don’t know much…yet

PCOS

The PA is talking of metformin and birth control

Isn’t that a diabetic medication? Why would I need it?

I’m too scared to ask. It cannot be. Liiiiike, say it ain’t so.

PCOS

My skin is breaking out.

My neck has gotten darker.

The irregular and painful periods.

The insomnia.

The crazy sweet tooth.

My hair has been thinner lately.

My testosterone is elevated.

The rapid weight gain. The struggle with weight loss. My frustrated efforts.

It all makes sense. It is not entirely my fault. I should not have been so hard on myself.

PCOS

I am a medical student on the other side of a scary diagnosis.

I think about all the ways I want my provider to show up.

I wish I had more time to process and ask my questions.

I wish my message on the patient portal was addressed.

I see medicine from a new angle.

I resolve to be a rock when I deliver an unsettling diagnosis.

To avail myself to my patient through the uncertainty and stages of grief.

PCOS

I scour every article PubMed has to offer. C.R.A.P style.

Something about inositol imbalance and insulin resistance. Metformin begins to make sense.

Something about fertility. I want to be able to have children.

With options come power.

I remember that I am still human. This body of mine is frail. I am angry and disappointed

Why me? I have always had a clean health bill.

When did things change and how did I not notice?

Why didn’t this PA tell me more?

Where do I go from here? What is to come?

Mary Howerton, Class of 2024

Your first climb started so young and performed. From so young you had to climb your way out of terrible memories, hard pasts, tough situations....

Read More

Mary Howerton, Class of 2024

Your first climb started so young and performed. From so young you had to climb your way out of terrible memories, hard pasts, tough situations. Rough childhoods or terrible families, military deployments that showed you the worst humanity can be. That first drink was a surprise, an oasis in a desert of misery. For the first time, you had numbness in your life, and you thought it was the perfect solution. Buddies drinking in barracks or in bars. Drinking culture at its prime, giving you permission to get numb.

Was your next climb the ascent? Noticing you drank more than everyone around you? Starting to drink alone, at home? Perhaps you thought no one would notice. Sneaking away from the family you had to find numbness again. You love them, it’s not them you want to hide from. The drinks you have don’t seem to be enough anymore. Higher count, higher proof, higher concentration to attempt the same high as before. For a time, you couldn’t tell which was the stronger drug- alcohol or denial.

You climbed deeper and deeper into addiction at that point. Physical dependence replaces any psychological one you had previously. Baseline levels just to not feel sick, but those levels made you feel bad anyways. Tremors, sweats. Cutting back but you couldn’t. Feeling stuck. The life you have and the life you want separated by the chasm that is withdrawal.

Climbing into darker and darker depths. And then that news. “We have run some tests and we have important news to share with you. You have cirrhosis or scarring of the liver. Based on your symptoms, your liver is failing to do its job. We will do everything we can to keep you as healthy as we can, but we need to start looking at other options”. In that moment the warm blanket of denial is ripped away. Cold reality sets in. The chill on the path you have set for yourself is so lonely and so cold. Regret is bitter. And there a decision had to be made; do you continue the road you were on, or do you choose an entirely different battle?

The road to sobriety was one of the toughest climbs you have ever had. While I might have some clue about what that entailed, only you know the strength it took to change it all.

Perhaps the most complicated part of this route was what lay ahead. Transplant committee meetings. Transplant lists based on scores. Review boards and waiting for a second chance. All the while your body fights every day to keep up. Fatigue setting in, skin and bones. Yellow and sunken eyes. The body a betrayal of the work you put in the last six months to fight for sobriety.

The days are long, but you keep walking. Your steps slow, and you notice yourself stumbling every few feet. Then falling to your knees. You can’t climb anymore, you think. Collapsing down. You can see the ascent, the end. But it is too far away.

I come visit you in the intensive care unit. Your body is failing, and we have hooked up to every machine we could to keep you alive until a donor is available. Intubated and sedated you lie there, holding onto life. I pull out my notes from my white coat, write down the newest numbers on how you are operating. Notes put away. I grab your hand. I plead and pray for a new liver for you. For a second chance at a mended life. We stay like this for a while before I let you rest for what will be the last ascent, the transplant surgery.

You received your second chance at life at 11:56 pm that same day. Keep climbing. You have already come so far.

Kenneth LeCroy, MD

There is an old joke that asks the question, “How do you want to die?” The answer is a quipping one: “I want to die...

Read More

Kenneth LeCroy, MD

There is an old joke that asks the question, “How do you want to die?” The answer is a quipping one: “I want to die like my grandfather, peacefully in his sleep. Not screaming, yelling, and in terror like all his passengers.” A silly joke asking a very important question.

One of the early steps in Stephen Covey’s book 7 Habits of Highly Successful People is to start with the end in mind. He means to begin by visualizing a life goal and then build foundations and processes that help to accomplish that eventuality. Those goals may or may not be achieved, but the eventuality of death will happen to us all. So how do you want to die?

I would like to tell you a great way to die, but before I get there, I have to tell you some stories.

In 1991 my oldest brother David had a dream that essentially pushed our younger brother and me to go on a five-week trip to and through Alaska. We drove to the Canadian border from San Antonio, Texas—and that was just the halfway mark. (We made it work, but this is not how I recommend traveling North.) Our first stop was Skagway, Alaska to do the fairly grueling Chilkoot trail, a 33-mile stretch of the Yukon Gold Rush. The elevation gain is incredible, with up and down sections repeating ad nauseum. We began the three-day trek with 35-pound packs and were out of food by the last day. On our second day, we were concerned about a group camping nearby—three friends, one in their late 70s, the other two in their 80s. We were discussing whether to share our food with them when we heard the distinctive sound of a bottle of wine opening! We later wondered if we should offer to help them at the pass itself…and they beat us to the top. Had we known we would have been asking them for their help throughout the trip as they were clearly living their best lives while ignoring the number of their birthdays.

We had done the trail. A three-day hike that was a great accomplishment in life. We sat in silence among debris and trash from me that had lived and loved and worked so hard and died one hundred years before us. A humbling moment.

Fast forward 10 days from there. We were in Denali National Park where cars are not allowed. Ingress is by yellow school buses to which the animals have acclimated. We had plans to camp for 7 days, so we packed heavy 55-pound packs and rode the bus for five hours before embarking on a flat 7-mile hike to our site.

The moment we strapped on the packs it was vastly different— I still use this illustration with patients about the benefits of losing 20 pounds. We trudged our way through thick high brush, calling out every 20 or 30 seconds “Hey Bear!”; walking up and surprising an Alaskan grizzly is not wise. After a rest break on the first day, we all struggled like crazy to get on our feet again. David in particular struggled, he slipped and found himself on his back with the backpack weighing him down, as helpless as an overturned turtle. Far from being angry, David laughed uproariously, and the three of us laughed continuously for a long time. From time to time over the years, we talk about that trip to Alaska and always include that moment.

Fast forward now to the Christmas of 1998. My family as a rule would gather for at least a weekend around Christmas to celebrate, and this Christmas was no different. I clearly remember my brother David asking me a question that puzzled me at the time. He asked, “You know that feeling you get when you pass out while you’re laughing really hard?“ I told him that I did not know what he was talking about, and I left it at that. A month and a half later on Valentine’s Day, there was another family gathering to celebrate my mother’s and my brother David’s birthdays (his 35th.) I was unable to go but my wife made it. She mentioned that David was experiencing balance issues and she had seen him hit a wall once while walking down a hallway. He assured everyone that he had seen his doctor and had an MRI pending. A few days after returning from that Valentine’s visit he had the MRI results—and an appointment his primary care doctor had scheduled with an oncologist. I was able to go with him to that oncology appointment. I was completely convinced that he had an acoustic neuroma—difficult to treat, but treatable.

David and I went into the appointment room together. It was a small exam room in the Cancer Treatment and Research Center of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Along one wall was a bank of X-ray view boxes and MRIs attached to the wall. Instantly I was disappointed in the center because they had clearly left the previous patients’ MRI up and allowed David and me to enter. I briefly glanced at the X-rays and could see an obvious large tumor…the previous patient was, as our Alabama relatives would say, an absolute dead person. I was approaching the end of my third year of residency in family medicine, and I knew this was a grave patient privacy violation. The physician eventually came in and began to talk to us and to my shock, quickly turned to the x-ray view boxes and directed our attention to the MRI. I had to ask the doctor twice to confirm that that was indeed my brother’s MRI on the wall.

David had a large glioblastoma multiforme in his brainstem. What he was describing as fainting when laughing out loud was pressure being put on the brainstem with Valsalva and shutting down brainstem function. Unfortunately, my prognosis was correct. He had a terrible brain tumor and only a few months to live.

After a biopsy, he received the best treatment at the time for that disease, which was radiation coupled with cisplatin. Futility was obtained quickly and by early June it was clear that he was beyond hope of a cure. He and his wife had their fourth child during this treatment regimen, and he had well over ten thousand people praying for him all over the world through his church’s network, and yet his health continued to decline. My wife and I were scheduled to graduate in July from our residency in Corpus Christi, and after the ceremony, we drove like the wind to San Antonio. David had been on hospice for a few weeks and was near death, slipping in and out of consciousness as we sped there.

When I arrived around 6 pm I saw David in his hospital bed, essentially in a coma, but he lightly squeezed my hand and seemed to mouth what he often called me, O’Kenny.

Sitting around David was his wife, my two sisters, my younger brother, my mother, and myself. We were a mix of somber and comforted, telling stories and occasionally laughing. As it approached midnight with my brother’s death rattle rhythmically sounding, we started recounting the stories of our time in Alaska. We started to tell the story about shouting “Hey Bear!” and laughed about the turtle that was David. We all laughed—the long and hard laugh of a family in pain together.

After a bit, just after midnight, we stopped laughing and settled into quiet. Total quiet, as we all noticed together that David had died.

There is much that is unknowable about the final stages of death. Many hold that hearing is one of the last senses to go, as some who have been in comas and recovered relay things heard while comatose. I believe David’s hearing was intact in those final moments. I believe he laughed, which pushed that pressure on his brainstem over the edge, and surrounded by love and family, my brother died laughing.

How do you want to die?

Do you want to die remembering wonderful moments? You won’t unless you make those memories and eschew working all the time. Do you want to die surrounded by love? Then live loving. If you want to die rich and unmourned, that too is in your grasp.

I want to die laughing.

Prisca Mbonu, Class of 2026

I learned so much that semester. I learned about the different ways a person can fall in and out of love, how to measure specific...

Read More

Prisca Mbonu, Class of 2026

I learned so much that semester. I learned about the different ways a person can fall in and out of love, how to measure specific heat capacity of a metal in Chemistry lab, the perfect step-by-step method to parallel park for my driving test, what medical specialty I would likely end up in after the grueling pre-med years and…about depression.

During that semester, I would become intimately familiar with the illness known as depression.

An illness that I had been largely unaware of throughout my life. An illness that I had brushed aside by the sheer will of what I often call “African stoicism,” a tough outer shell, impermeable to hardships and unperturbed by the twists and turns of life.

Depression? Who is that?

That semester. The lack of appetite. The loss of interest in life. The avoidance of friends and classmates. The skipped classes and missed meals. The unexplained sadness, unprovoked irritability, and unstoppable tears.

All signs pointing towards depression. All signs we could not see. All signs we would not see.

That is, until they became signs that refused to be ignored.

After endless probing and pleading, you finally confide in me. You tell me that you need help. That you have been struggling for a while. That you are sad all the time. That you don’t see the point of living anymore.

The last part breaks me.

You tell me.…you think you might be depressed.

It turns out that while I have had no experience with mental illness, you’ve had far too many. Enough that simply uttering the word “depression” elicits a visceral reaction.

You have experienced the shame and isolation associated with seeking mental health care. You have seen family members live silently with mental illness, afraid of whispered rumors and the inevitable judgement of others.

Unlike you, I did not grow up hearing words like depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder. I am ashamed to say that I knew nothing about your illness at the time.

But I am determined to get you through this “hurdle.”

Straight A’s. Type A. A perfectionist. High achiever. This is simply another question to answer. A difficult but requisite college course to travail.

I do my research.

Exercise. We walk and walk. We talk and talk. Until our legs hurt and heels blister. Until we have exhausted both our words and our selves.

Diet. No more skipped meals. We are first in line at the cafeteria. A healthy breakfast to start the day. Lots of fruits and vegetables. Don’t forget to stay hydrated, always.

Music. We explore the rich music of my culture. I teach you the lyrics and dance moves. You marvel at the vibrancy and uniqueness of Afrobeats. I marvel at the fact that the music I took for granted could be so deeply appreciated by another.

K-dramas. We watch all the good shows, all the bad shows, and of course, everything in between.

School. We study together at our highly coveted spot in the library. You help me with art projects. I help you with Calculus I.

Everyday we live in this bubble of our own design.

Has the ever-looming cloud of sadness passed? Are you smiling more these days?

Or am I imagining the slight curve of your lips? Do I hallucinate the faint gleam in your hazel eyes?

I must have. Because you aren’t better. Distracted? Maybe. Not better.

We have been pretending that nothing is wrong. But ignoring an illness does not make it go away.

I am crippled by the fear that I can’t help you. That I am not enough. This thought terrifies me.

You are my roommate. Brought together by luck of a random draw and yet, you have become so much more. You are my friend.

I have learned to always push through obstacles, fearless and determined. But this isn’t just an obstacle. Your depression isn’t just a problem to be solved. A thing to bulldoze through with my endless optimism and stoicism. One more adversity to face boldly with my shield of resilience.

I bring up the next logical option. It’s time to seek help from a professional. Therapy, maybe?

You resist the idea. I knew you would.

But I persist. And reluctantly, you agree.

We walk and walk. But this time, we are not simply taking endless loops around a geese-invaded lake. This time, we walk with a purpose. This time, we walk to get you the help you need.

We walk, but don’t talk. Instead, we allow our minds to wander in an odd yet peaceful silence. And then I wait.

Your first counseling session is hard. But week after week, without fail, we continue to go. We continue to walk. I continue to wait. Now we have a new routine.

This time, you truly seem better. I am numb with relief.

Because in those months, I couldn’t tell you how scared I was. Afraid that our efforts would be inadequate. Afraid that you could sense my ignorance about your illness.

Thank you for letting me in. Thank you for getting out of bed at my insistence. Thank you for trying.

And thank you for allowing me to care for you.

Kavneet Kaur, Class of 2023

Character Description Kavneet: A naïve 3rd year medical student working a shift in a rural Emergency Department at the time of yet another COVID surge....

Read More

Kavneet Kaur, Class of 2023

Character Description

Kavneet: A naïve 3rd year medical student working a shift in a rural Emergency Department at the time of yet another COVID surge. Must work shifts for 28 out of 31 days this month. Tired, but ready to work and take on a challenge. Always hopes for the best and tries the see the good in a bad situation.

Scene: It is month 8 of 10 of my Emergency Medicine rotation and delta variant reared its ugly head.

====================================================================

[Cruising down the highway at the crack of dawn with the window rolled down, I let the cool, crisp air wake me up. The radio is screaming on repeat: “The death toll from COVID-19 is increasing day by day… Delta variant seems to have world leaders worried of yet another spike in cases”. As I pull into the parking lot, two deer cross in front of me near the entrance of the hospital. You don’t get that in the city.]

Hour 0

KAVNEET: “How is this shit still going on?” I grumble to myself as I walk over to greet my attending in the breakroom. I notice the tracker board with the list of current patients… just when I thought I was going to have a ‘Q word’ day.

“Q word” means “quiet”, but you don’t dare say that word in the ED unless you want all your staff cursing you out an hour later while being knee deep in patients that decided to take a trip to your emergency resort.

I overhear the overnight attending pass off a patient to my attending physician, who in disbelief remarked “This was the same patient I had on shift two days ago.” The patient is COVID positive and is currently waiting to be transferred to another facility for more intensive care, but no hospital nearby is accepting patients.

They have now been in isolation for more than 72 hours. Imagine a 6-foot by 6-foot room with white walls and no windows. No human contact outside of nurses coming in to give you meds or adjusting ventilator settings. Sedated. Looking more machine than human. Listening to the music of the vital monitor beeping similarly to a ticking clock, amid chaos happening in the room to the left and to the right of you. Lifeless.

It is quite literally the closest thing to solitary confinement without being imprisoned.

My trance breaks as we rush through the remainder of the patient list. I notice there are others waiting more than 40 hours needing to be admitted to the second floor for inpatient care.

Here’s the thing that the public tends to forget- there are still a portion admitted patients in need of critical care, who do not have COVID. This could be your grandfather having his first heart attack, your significant other that just got into a car crash or is having a miscarriage, or your child that is about to slip into a diabetic coma.

And the fact of the matter is that there may not be a place to put them or stabilize them. Even if we can, they are still left waiting for another hospital to “accept” them to get the care that they need.

Why does someone need to be interviewed to see if they are sick enough to be treated? How does that make sense?

Hour 2

KAVNEET: More patients are checking in. COVID patients get priority, especially if they have a below desired oxygen level. In other words, “priority” means you can be put in a room with an actual door that closes. What do we do when those rooms run out you ask? I pray to God. You pray to whatever Higher Power you believe in or just hope for some good vibes. “We have NO rooms open for COVID patients!” I hear the charge nurse scream as if it was not obvious. Though by the look in her eyes, more a scream of frustration than one to state facts. Let those prayers begin. We now have no option but to fill in these makeshift “rooms” with possible COVID patients. Picture a room divided into smaller sections by a shower curtain instead of an actual door. I try to justify it to myself as, “well, it’s not like there is any other place we can put them, and we can’t just stop seeing patients.”

Hour 3

KAVNEET: I do the best I can to help my attending and the staff see patients. At one point, I go to the front to help triage patients, some of whom had now been waiting for at least an hour. Our triage room is quite literally the size of a closet, so you can imagine how this was about to go.

With my head held high, a N95, surgical mask, and face shield, I march into the lobby and scream the first patient’s name to bring them into our broom closet. Yes, scream…it is that chaotic. I ask what brought them to our ED today. Cough, fever, shortness of breath? What a shocker.

“Have you been vaccinated?” I question with skepticism. No? Surprise, surprise. I proceed to get the vitals. Blood pressure 142/94… eh, won’t kill you, temperature 99.8… low-grade fever, heart rate 104… tachycardic, oxygen saturation 92… mildly hypoxic. Yep, this is to be expected. Ok now to swab for COVID.

Like clockwork, now onto the next one.

Hour 3.5

KAVNEET: We officially maxed out on the makeshift rooms, but we still have a lobby full of unseen patients. “What can we do? I understand we don’t have any space to put them, but we can’t turn them away,” my attending physician shouts through his N95 to the charge nurse as he rushes to check on a critical patient that just came in with low oxygen saturation. “PAGE RRT STAT”.

34-year-old female, with oxygen saturation in the 50s.

As my attending and others work to assess the gravity of the situation, the rest of us manage to add two gurneys and a chair… three extra spaces in the hallway of our small boondocks ED. If a code blue walks in through the door right now, we would literally be doing it in the ambulance bay outside of the hospital. Totally code compliant.

I rush back to the critical patient that was brought in. Everything and everyone moved like an assembly line. Prepare the meds, sedate, paralyze, intubate, get out. I open her chart and glance through it. She is a healthy young woman without any health conditions. She has had COVID-like symptoms for 2 days and began to develop shortness of breath overnight. So why is she this bad? Something is not adding up…Vaccination status? Unvaccinated.

As we exit the room, the front door almost knocks me down as the medical director of the Emergency Department darts in through the door. Before I can process, monitors start going off. BEEP BEEP BEEP! The patient that we just intubated… a bunch of staff rush in and one of the nurses’ pages RRT again. Oxygen saturation is 70. I stand outside the room as I see the panic in everyone’s eyes. There’s simply no time for this right now.

My attention diverts behind me as I overhear the charge nurse and medical director calling hospitals from DFW to College Station to find beds so they can move our current patients out to add new ones to the trenches. The medical director even made a personal call to the CMO of the hospital system. Little did I know that in the last several hours, we were still getting calls from the transfer center to accept patients from Kansas.

Hello? What happened to the entire state of Oklahoma?

Hours 4.5 to 9

KAVNEET: We come up with a plan to open a currently unused space on the second floor to put some non-COVID, lower acuity patients. One of the nurses told me this is the first time since the pandemic began 1.5 years ago this was being done. And for the first time since beginning my shift, I force myself to find a moment to stop and take in what is going on around me.

Do you think if an unvaccinated person saw face to face what it looks like to have more than a “COVID cold”, they would change their mind about getting vaccinated?

I often think about that young lady on the vent. If she made it off, her life will never be the same.

On a systemic note, I’m still trying to grasp how we got here? I see nurses, techs, RTs, pharmacists, radiology techs, and physicians running around the hospital trying to do the best they can, trying to solve problems that were created by this system, trying to juggle tasks out of the scope of their practice on top of their normal duties because there is no one else there to do it. I am appreciative of how hard each team member worked in our small ED that day. They are the true embodiment of perseverance and fight.

On top of dealing with a public health crisis, the unfortunate reality of working in a small ED such as this one is that patients are at risk of dying, simply because they cannot get to another facility for more intensive care. Bigger city hospitals will not accept more patients because they are also being bombarded with COVID, and statistics show that most of these patients are also unvaccinated. Even then, at least the bigger hospitals are equipped with resources and specialists to handle the surplus. To put it into perspective how smaller, boondocks EDs are affected, if you are unfortunate enough to come on the wrong day, your options are to talk to someone through an iPad or get transferred to another facility that has someone physically there to take over your care. Often, it’s the latter and we are 40 minutes from the nearest big city hospital.

If being vaccinated means less stories like what you just heard, less burnout for the people who are tirelessly and endlessly taking care of you and your loved ones, less loss of the ones you hold close to you and heck, maybe even you yourself. The question I then pose to you is: If you do not have a legitimate medical reason to not get vaccinated, what is the hesitation to get the vaccine? Whether you are pro-vax or vaccine hesitant, we can all agree that we are mentally and physically tired of this and want life to go back to “what it used to be”.

====================================================================

**This piece was a finalist for the inaugural production of Stethoscope Stage

Sarah Lyon, Class of 2023

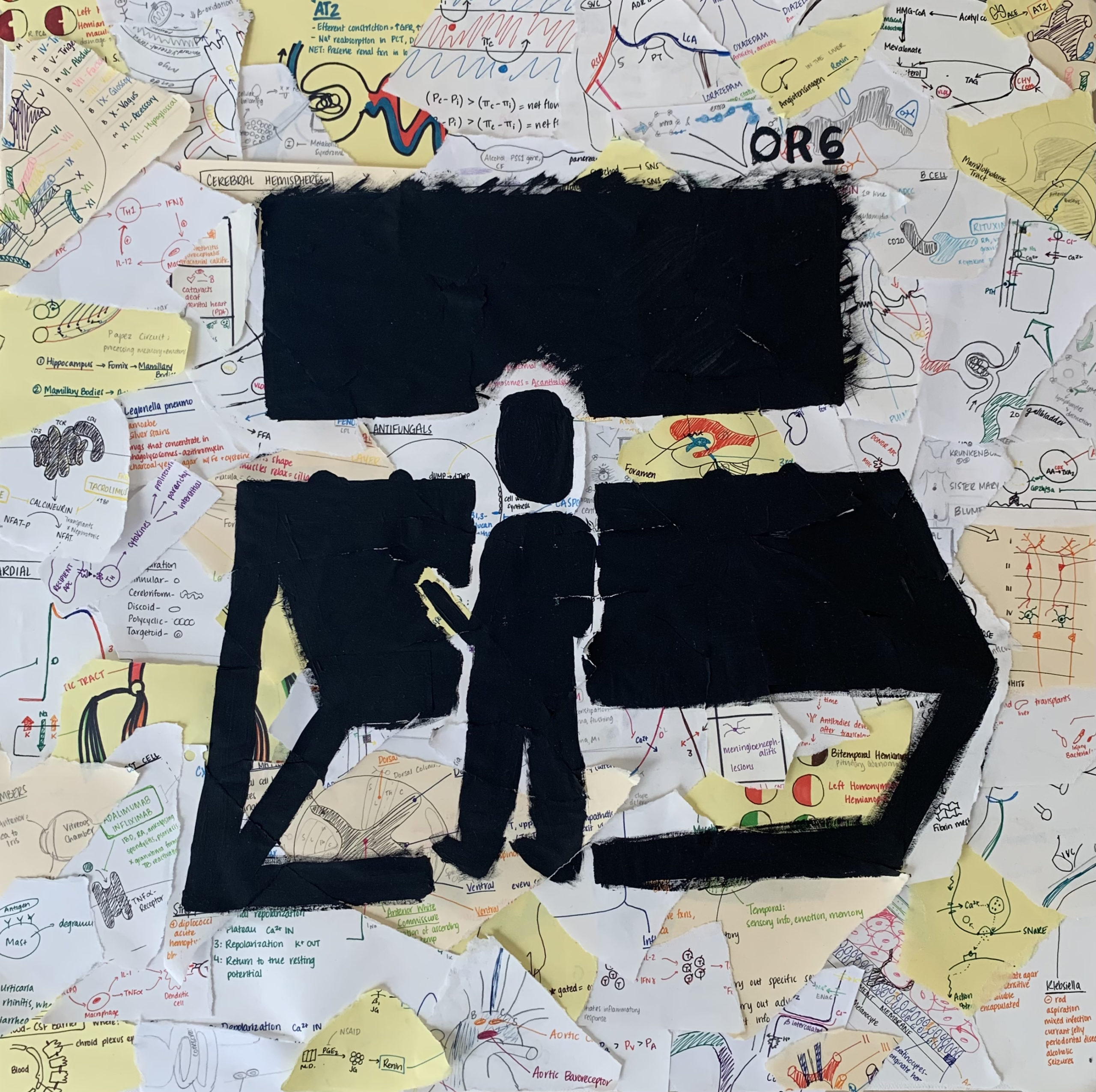

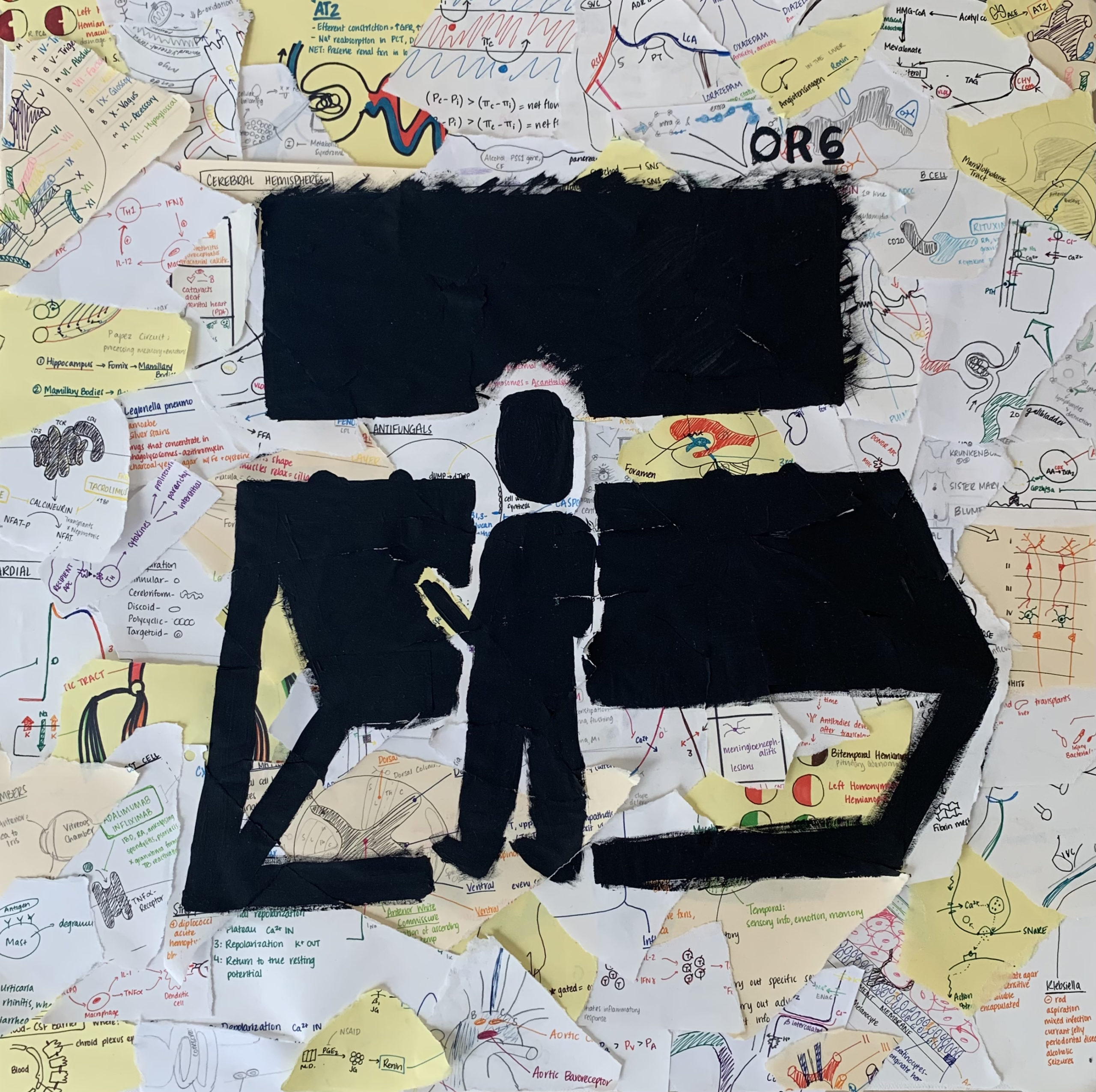

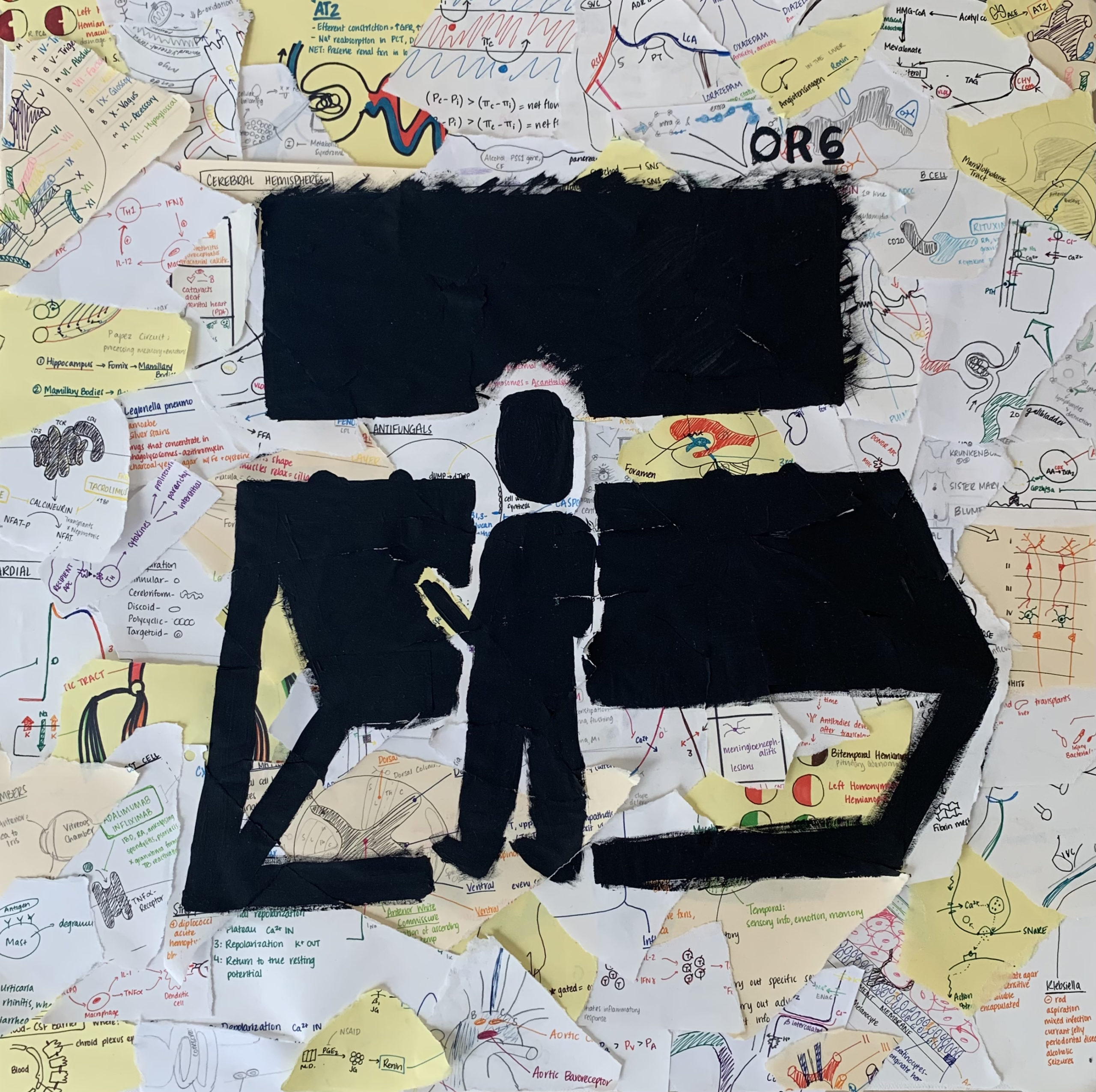

paper and ink, tape, and acrylic paint on canvas A Medical Student’s first time scrubbing into the OR. Snippets of everything they learned during didactics...

View Art

Sarah Lyon, Class of 2023

paper and ink, tape, and acrylic paint on canvas

A Medical Student’s first time scrubbing into the OR. Snippets of everything they learned during didactics flashing in their mind. Looking into the unknown darkness of OR 6, unsure of what is to come. Will they be prepared and competent enough to provide exceptional, empathetic patient care?

Sarah Cheema, Class of 2023

Sometimes I don’t know if I can handle another one. Another uncomfortable pause, another sudden shift in body language, another dance of “did you get...

Read More

Sarah Cheema, Class of 2023

Sometimes I don’t know if I can handle another one. Another uncomfortable pause, another sudden shift in body language, another dance of “did you get the vaccine” and “no, it was too quick,” “no, I don’t know what’s in it,” “no, and I will not.”

I wish it were just a simple question and an answer – like all the other checklists in my patient visits. I can ask a patient about their home life, diet, drug use, and sex life and get an answer so nonchalant I have to double-check that they’re listening. But, the same person might nearly freeze when I ask about the vaccine. It’s almost as if I can see their spine straighten and their muscles tense, prepared for Battle with the Know-It-All Doctors (and their Students). Their walls come up and suddenly we are miles apart. That’s what I hate the most. Not even the uncomfortable conversations, but the sudden distance, the instant formality as if it is no longer two people speaking in a tiny room but instead, a hot-seat interview on a news channel.

This is not to say they are all the same, they are definitely not. There are those genuinely seeking information, truly torn between a desire for safety and a fear of complications unknown. There are those paralyzed not by their own fear, but their daughter or sister’s fears. There are those with bookmarked Facebook posts, ready to brandish a vaccine horror story like a knife. There are those who I wonder about the most. Those who strongly and firmly state “no” and offer no further engagement. Then, there are those who I feel like begging. The 34-year-old pregnant woman, the diabetic 65-year-old headed for dialysis, the elderly 83-year-old in the emergency department. With them, I walk the thin line between persuasion and disillusionment, hoping I don’t trigger the dreaded blank stare. I think of my unfortunate patients. The 31-year-old guy who was finally cleared to go home after a 60+ day hospital stay, only to suddenly pass away from hospital-acquired COVID 1 day before discharge. Sometimes, I refuse to walk the line at all and I simply move on.

Honestly, it all depends on the day. On good days I feel kind and patient, mindful that we all crave the same health and freedom. Other days, I am tired and frustrated. Tired of all the cracks in the system, like the fact that students aren’t supposed to see COVID positive patients yet I spent countless days in the ER listening to the lungs of patients incidentally found COVID positive 15 minutes later. Tired of spending my days as a medical student next to a doctor on a laptop telehealth visit instead of floating between exam rooms as my predecessors did. Tired of the relentless acne from wearing a mask for 8-12 hours daily. On these days, my brain reverts to its primitive schema mode and determines the status of each person: either With Us or Against Us. I know, I know that this is not the reality. I know that everyone supports healthcare workers and vaccine hesitancy is remarkably multifactorial. Still, compassion fatigue is real and it permeates hospital halls like its own disease.

I try to imagine what the vaccine is to them. Often, it seems impossible we are talking about the same thing. What is to them a dreaded and dangerous trap is to me a golden ticket, a precious shield in a chaotic war zone. It absorbed some of the helplessness that we were drowning in. It gave me a guiding light, a dream of an education unmarred by a new virus. The “truth” outside the politics, fear, and hopeful dreaming, probably lies somewhere in the middle. The vaccine is neither a magical cure-all nor a manufactured lie. It is just a little piece of nucleic acid that travels into cells to become a protein that WE HOPE MAKES A DIFFERENCE.

====================================================================

**This piece was selected and performed at the inaugural Stethoscope Stage production in 2022**

Shanice Cox

Written & Performed by Shanice Cox [audio m4a="https://mdschool.tcu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Take-a-moment….m4a"][/audio] Take a Moment Chapter I: Obstetrics and Gynecology Take a moment... to breathe Take a moment...to...

Read More

Shanice Cox

Written & Performed by Shanice Cox

Take a Moment

Chapter I: Obstetrics and Gynecology

Take a moment… to breathe

Take a moment…to seize…this moment that sits before you

Take a moment… to see,

beyond the gown, the drape, or the anatomy

Take a moment… to listen to the history,

To the crackles in her speech, to her hesitation,

To the hum in her pause, to her tone’s vibration,

Take a moment… to view

What it is that lies in front of you

As her hand is carefully positioned behind her head,

And the gown is respectfully placed,

while ribbons gently touch the side of the bed,

and the slight embarrassed flush of her face

Take a moment…to view

the contour of her breast

Clockwise and counter

view symmetry, asymmetry,

are you still there?

Or has she become a mindless exercise of your checklist,

color, texture,

Are the nipples inverted,

Is discharge produced,

are nodules immobile,

is her quality of life reduced?

Take a moment… to be silent

With differentials and questions and familial history pooling in the mind,

For you must make space in this stillness of time,

To deliver a news that may shift the course of this rhyme

Take a moment…to reimagine,

That this couldn’t be you,

That you couldn’t be the one

To look in her eyes and deliver the troubling news,

It was the life you wanted,

The only specialty you knew,

But over the course of your training,

The weight of this burden grew,

Take a moment…to revisit

Those feelings that once were,

Filled with such promise,

That now feel so obscure,

Take a moment…to gather

Your thoughts,

your desires to serve in this space,

To counsel, to teach, to empower, and to share a thoughtful embrace,

To right the wrongs of centuries-old medical practice

With dignity, humility, and grace

You approached the field,

With only the thoughts of positive outcomes,

But failed to consider…when there wasn’t one,

Your story did not capture the woman who fell ill,

Or when the fetus had been delivered,

Cold, pulseless, and still

Take a moment…to process

How you revered in maintaining the health of the womb,

But after seven days on the service,

This vessel of life,

Evolves into a hollow, pear-shaped tomb,

Take a moment….to reconsider,

What life would be if you made more room,

To till the soil of your garden,

And allow for the seeds of destiny to bloom,

Take a moment…to look

Into the mirror and see what you’ve become,

Because there in that reflection,

There is a slight resemblance of someone,

Fragments of the old, but glimpses of the new,

Moments that reflect past passions,

but notes of what they had morphed into,

This desire to serve extended farther than that of the woman’s womb,

And in this infinite Eden of possibility,

My brainchild found room

Chapter II: Urology

Take a moment…to reset

To look at this rotation anew,

Because what you had been searching for,

had somehow found you,

It began with a knock on the door,

And a sheepish reply “You may enter”

Unconsciously I shift my attention to the woman,

But she is not who sits at the center

Take a moment…to view,

The air of defeat in the slouch of his posture,

Take a moment ….to recognize his courage to seek a doctor,

He peers up at you,

An emptiness in his gaze,

His wife quickly rushes over to hold his hand,

To somewhat mask the depth of his dismay

He tells me of their journey,

And how they’ve tried for years and years,

Until they sought the help of medical professionals,

Who would somehow ease their burgeoning fears,

He spoke of her strength,

Navigating conversations about her ability to conceive,

He spoke of her courage,

To defend and protect her family without reprieve,

Take a moment…to notice

The pain that continues to resurface,

And all that they had been through,

The waning support of their loved ones,

The constant judgement and ridicule,

Yet she sought answers,

she completed all the tests,

But when they all came back normal,

She entrusted him to do the rest,

Take a moment… to breathe

Take a moment…to seize…this moment that is before you

Take a moment… to see,

beyond the gown, the drape, or the anatomy

Take a moment… to listen to the history,

To the crackles in his speech, to his hesitation,

To the hum in his pause, to his tone’s vibration,

Take a moment… to view

What it is that stands in front of you

As his hand is carefully positioned atop his head,

And the gown is respectfully placed,

while ribbons gently touch the side of the bed,

and the slight embarrassed flush of his face

Take a moment…to inspect

the meatus and penile shaft,

Testicle, epididymis, spermatic cord,

Give yourself this moment to perfect your craft,

Are the testes symmetric,

Is discharge produced,

Are prostate nodules immobile,

Is his quality of life reduced?

Take a moment…to reimagine,

That this could be you,

That you would someday be the one

To look into his eyes and deliver the hopeful news,

It was the life you wanted,

Combining the admiration of a specialty you once knew,

Yet a new seed was planted,

With a flourishing destiny coming true.

====================================================================

Artist Statement:

This piece is dedicated to my grandmother, Claudette Cox-Brown, who exposed me to the intricacies and

delicacy of reproductive health. She served as a nurse midwife in Jamaica, England, and New York and shared with me so many

precious narratives of femininity, obstetric care, and the hardships of navigating pregnancy whether wanted or unwanted in

years past. Over time, the initial intrigue of her stories sparked an interest to pursue a similar path, and it followed me for a large

portion of my life. It paved the way for research opportunities in college focused on breast cancer, a medical mission’s trip to

Durban, South Africa focusing on the obstetric care of mothers and babies affected by HIV, my first career as a medical assistant

at an OB/Gyn office in Washington DC, and even the acceptance of a medical fellowship whilst in medical school, and for that I

am truly grateful.

However, this dream of mine to be an OB/Gyn never included the emergencies that happen in the delivery room. And

when things go awry, it happens fast. In my many experiences, I had always seen the outcome of healthy mother and healthy

baby, but never considered the possibility of losing either. My time in the longitudinal clerkship exposed areas of my journey that

I seemingly avoided, or hadn’t been privy to, and placed me in an emotional headspace I couldn’t escape. The beloved field that

had my heart for so long, had cemented wounds that had me question what the next step would be. In this poem, I address

some of those hardships, but also this love that I have for reproductive medicine transforming into something more, something

that created a space for old passions, but hopeful futures.

Urology has been that great awakening for me, not that I had slept through the life of undergraduate medical

education, but just an opportunity to see things both old and new with renewed purpose. Traits and behaviors that I had

perfected in my pursuit of being an obstetrician, have crafted my mindset about practicing urogynecology. I feel hopeful that my

interests in gynecologic procedures that focus on health after childbirth such as pelvic floor instability and urinary incontinence,

along with surgeries with the intent to tackle conversations that have are attached to social stigma such as female genital

mutilation and transgender medicine, can be cultivated in this field.

This poem takes you on that journey with me, the journey of facing those emotional hardships with the patient, and

within myself. Take a moment was written as my reminder to find some time, even just for a brief moment to be in that moment.

It is a mantra I use to escape my racing thoughts, to reconnect with patients, to observe, to reflect, and be mindful of the here

and now and sacredness of the space that my medical journey has afforded me. Take a moment though dedicated to my

grandma is a thank you to each obstetrician/gynecologist, midwife, nurse, charge staff, medical assistant, phlebotomist, practice

manager, and sanitation engineer that inspired and prepared me to seek and gain knowledge about every aspect of feminine

health. It is also a commitment to each urologist/urogynecologist, resident, and therapist who have accepted, mentored, and

exhibited patience and support as I worked to figure out the journey that lies ahead.

Shelby Wildish, Class of 2023

Character Description: Medical Student. Female. Late 20s. Eager to learn medicine, self-critical about self-expectations, general baseline tiredness. Wearing hospital issued scrubs, white coat, old worn-out sneakers....

Read More

Shelby Wildish, Class of 2023

Character Description: Medical Student. Female. Late 20s. Eager to learn medicine, self-critical about self-expectations, general baseline tiredness. Wearing hospital issued scrubs, white coat, old worn-out sneakers.

Scene: In Medical Student’s apartment living room. There is a big, colorful, soft chair with armrests in the middle of the room. Beside chair there is a standing full-length mirror. In walking distance from chair is a table, with a lamp, a cell phone, and a laptop computer. There is a rug on the floor and a small footrest.

====================================================================

[Enter Medical Student – she walks towards a chair, stops, turns to face mirror. She looks exhausted.]

MEDICAL STUDENT: You did it. You’ve made it to the end of another busy day. (Moves to sit down in chair, pauses to look down at feet) Damn, my feet hurt. I don’t know how Dr. Barterman does this all day. Walking up and down those long emergency room hallways, never getting a chance to sit down. It’s her shoes, has to be. She has some of those fancy clogs I’ve seen other docs wearing. I need to get a pair. Well, one day…(looks at old sneakers, then up at audience, shrugs)…when I can afford it.

Time to reply to the messages that came while on shift. I bet it’s the college roommate group chat blowing up about the recent girl’s Facetime chat. Another hangout without me; more group memories made without me. I find it interesting how quickly during quarantine it became the “norm” for social interactions to be almost entirely through computer or phone screens. Just shows human adaptability I guess… (Sits quietly, scrolling on phone, to self) I don’t even know what the update is about Amanda’s baby or Susan’s postponed wedding plans. I really need to call them – add that to the long To Do list.

(Looking at phone, slowly smiling then laughing aloud) I can’t believe they remembered that story! That was so long ago.

(Directed to audience) So, once I was dared to jump in frog fountain and then slipped while on the wall and fell face first into the water. (laugh, looking back to phone, nostalgic) we were all such idiots in undergrad. Such fun, but such idiots. I wonder what brought that up in the chat? (directed to audience) It feels good not to be forgotten. I remember this one time that Amanda, Susan, and I snuck into my brother’s house and stole his car during a snowstorm. Us three freshman girls, just trying to do some car drifting in the supermarket parking lot. I definitely need to remind them about it. (start typing on phone, to self) Too funny. (phone dings with notifications, medical student sits quietly, smiling and typing replies to the group chat.)

(Smiling, student puts phone down, looks off into the distance, demeanor changes to one of concern. Look around room, pick up phone and begin typing)

Guys, did you hear about those mass graves for unclaimed patients on an island near New York City?

(sits quietly)

(Irritated, speaking to audience) How can I be laughing when such things are going on in the world? I should be reminding my friends about the situation at hand. Bringing the conversation back to the patients, back to the families, back to the healthcare workers and back to COVID-19. (stand up, pacing and talking to self) Remember your reality. Remember the world’s reality. You wake up each day, and are reminded through new articles, research journals, social media posts, videos, and patient stories of the one sole focus – COVID. Don’t forget it has caused schools to close, businesses to shut down, economies to crash and nations to close their borders. It has caused millions to become unemployed, thousands to become overworked and all to become fearful. It has killed. It is killing. And it will continue to kill.

How dare you laugh? How dare you forget momentarily. (phone dings, student walks back over to the chair, glances at it, reads it, places it face down on armrest of chair, without replying.)

And you, you underestimated this virus’s capability, initially nonchalantly saying {in a mocking voice} “Oh, it’s just another influenza-like infection.” You felt a need to have a reassuring answer for concerned family members. When really, what you should have just said: “what do I know, I’m not even finished my second year of medical school.”

You incorrectly, and almost arrogantly, claiming it only affects the elderly and immunocompromised. Have you temporarily forgotten that you have three grandparents? Think of Nana, of Papa, of Grandma. This virus could take them from you. You are guilty of blissful ignorance. How lucky are you to be so far disconnected from any serious, immediate personal consequences that you have the luxury of having moments where you forget about everything, all things COVID-related. You’re lucky. Your family has been safe. Many families can not say that.

(walk slowly back to the chair, sit-down, pick-up phone and begins speaking while typing) The first patient this morning was a pleasant young guy, maybe 30. (To audience) Not that bad looking either. (back to phone) When we saw him, he was making jokes, laughing, even flirting with nurse Kelly… But you could tell he was having a really hard breathing. (To audience) His face was so pale. (back to phone) We got his oxygen levels. It was 86%. Dr. Barterman thought it was COVID and admitted him to hospital. That’s bad news.

(put phone down, stand up, start walking over to the table, stop, to audience.) At the end of the shift, we heard he wasn’t doing well. They found pneumonia in both lungs. He would probably need to be put on the ventilator. And the crazy thing, he doesn’t have any chronic medical problems. He runs marathons. He doesn’t do drugs, doesn’t smoke. He hangs out with his friends, has a dog. And before the quarantine, loved exploring the city. He is a healthy guy. Well, was a healthy guy.

Was a healthy guy.

(continue walking to table, pick up computer. Walk back to chair, sit down with closed laptop on lap.)

I can picture him, before all this COVID stuff, with a group of friends at a brewery. Joking around, laughing. Maybe even having one of those moments when you laugh so hard that you almost fall off your chair in joyful pain. I bet he is the type of guy that looks for the good in the moment. I bet he would tell you not to beat yourself up about reminiscing, almost as if encouraging you the laugh. You feel the sad, the guilt, the hard times, he would want you to feel the good too.

Isn’t that human nature? To feel. Emotions protect against apathetic eyes. Apathy has no past to base experience on. From feeling nothing for nothing, is no life at all.

(pause, look off in the distance for a while. Then re-center, and open laptop, click on a few buttons, slowly read out loud as if reading from phone) The FDA has approved the COVID-19 Pfizer vaccination.

Could this be it? A light at the end of the tunnel. A chance to get some element of normalcy back in life.

(stand up, beginning dialing on the phone, lift phone to ear, pace around) I have to get it. I need to get it for my family, for my patients. I need to get it so I always remember. Remember what COVID has done… what COVID is doing.

Hello, Dr. Barterman. Hi. It’s me, Savannah… Yes, I just saw the news article… I know! … Yes, it’s all so exciting! … It’s what we were hoping for… I can’t wait for when I can get it. Can you help me register? … Great, thanks … Of course I remember him… he what? … when? … Thank you for telling me.

He was healthy… was.

====================================================================

**This piece was a finalist for the inaugural Stethoscope Stage production

Patrick Powers, Class of 2024

Sometimes, it is nice just to sit and listen to the wind rustle the leaves. The cooling temperatures linger in the air like a prelude...

Read More

Patrick Powers, Class of 2024

Sometimes, it is nice just to sit and listen to the wind rustle the leaves. The cooling temperatures linger in the air like a prelude to the winter ahead. I never thought I would find myself here, and I cannot help but smile through tired eyes. How many times have I missed the movement of life around me because of the movement around me? The enigmatic distractions surround us, poisoning the purity of the simple beauties of life. I admire the leaves in the fall. Of course, their color change inherently captures my attention as a reminder to stop and ‘smell the flowers,’ in a similar way a set of olive-green eyes might remind me to sleep, remind me that I have to eat three times a day, to try not to clench my teeth, and that, really, it will all be ok. In the end, there is an undeniable elegance to the falling of the leaves; a gentle but self-assured poise to each and every leaf that, when the time is right, plucks itself from its roots, and bravely sets sail on its solitary, yet sui generis voyage. The time must come for all leaves to embark on their journey, and though the trek may route through a previously undiscovered, and albeit, arduous, path, just as one cannot stop the leaves from changing colors, this too, embraces its own inevitability. How valiant, to stare down the fear of falling, to trust the make of their ship, to sail alone. Their destination is clear, their conviction clearer. The winds may blow, swaying their ship, aggressively rocking the foundation in an unrelenting manner. But, clever as the leaves are, flow with each windy blow, like water around a stone, never deterred from their ultimate goal, but ebbing gently with each test from the wind. No matter how hard the winds may blow, how laborious each challenge may appear, or how many bruises each leaf must endure, just as one cannot stop the leaves from changing colors, this too, embraces its own inevitability. As the leaves quietly, yet confidently, make their way to the ground, leaving behind the branch which had been their home for so long, so too must we all embark on our own journey. Which then begs the question, what is the ground? What is the ultimate destination? Worry not, the end is neigh. Rather, memento mori, only in as far as it gives purpose to life. For what is light without darkness, peace without war, and love without hate.

Perhaps I, too, can learn to be more like the leaves. The fears seem insurmountable, of being left behind on the tree, of falling, of never having the grit to jump when my time comes, of oblivion, cascaded by volume of inexplicable worries that flood every available space in my mind. I am sure the leaves feel similar. How beautiful that expedition must be, though, I think to myself; to experience those tests of life. The wind, with its capricious and fickle self, brings the blowing challenges that provoke us to breathe deeply and suck the marrow of life with each deliberate adventure. We are all meant to thrive so Spartan-like yet gentle, as the leaves do, staring deep into the eyes of falling, knowing we were made to live the life set forth in the path that is unraveling itself before our very eyes, that the make of our ships can and will endure the journey, and to jump, bravely and boldly, heart racing, with a smirk. Perhaps that smirk is to spite the inhibitions, perhaps it is because of the joy of finally jumping from our branch, or perhaps both. Sometimes, it is nice just to sit and listen to the wind rustle the leaves. I cannot stop the leaves from changing colors, and I cannot stop the fear that lingers in my mind. When I think about it, none of that even matters. My heart could flutter, butterflies flapping in my stomach, as I wipe the sweat from my brow. What matters is that we jumped anyway. We jumped off our branch, flying into our odyssey, highs, lows, and in-betweens, tears, laughs, and far too many unforgettable memories to recount, living the life we were meant to live, so that when it comes time to meet the ground, we will not discover that we have not lived. So here we go, with ill-fitted blue scrubs, a set of scuffed-up clogs, and a little too much caffeine, I catch a glimpse of myself in the sliding front doors of the hospital; tired-eyed smile as I sneak back into the resident’s lounge, just a leaf, riding the wind.

Peter Park, Class of 2025

When I was little, I spent my pre-teen summers with my grandfather in Korea. He was a retired salesman who spent his time coaching the...

Read More

Peter Park, Class of 2025

When I was little, I spent my pre-teen summers with my grandfather in Korea. He was a retired salesman who spent his time coaching the local high school soccer team. In the hot, humid summers, he would coach me in an equally intensive sport: gardening. His backyard spanned half an acre of trees, ferns, and cabbage. But his most labored love was his grapevine. Together, we built fences eight feet tall, allowing for her to expand her leaves reaching for the sun. She protected me from the heat like green clouds in the sky, dropping sugary fruit from the heavens.

One day, my grandfather handed me garden sheers with large rusty blades. He said we would prune vines that day. Unsure of what pruning was, I followed his direction: cut each branch he pointed at. My sheers would slice the darkened bark and reveal a white-greenish core, where glistening sap dripped at the center. The grapevine’s branches would fall to the floor with a thud and all the grapes would scatter like marbles.

My grandfather pointed to various branches of the vine, “This one is infected. This one has been eaten by insects. This one is too small.” I nodded with each response but could not understand the differences between the branches we cut and the ones we spared.

We came onto a large branch that was sturdy and strong. Its bark was like the thickness of a tree and would not break under my grandfather’s bare hands. I prepared to move on to the next branch until my grandfather placed his hand on my chest. He pulled me to the branch and said

“Look, it’s dying.”

I was confused. “How? It’s so big. It must be alive.”

He considered, “You’re right. It is alive and growing well. But, if we allow this one to grow, it will steal the energy from the main branch, and go in a different direction. That’s not where we want to take it.”

For the first time, I saw the grapevine as one connected system, and I understood. This sturdy branch deviated almost exactly at a 90° angle. Like a rebellious teenager, she wanted nothing to do with her parent. Allowing this one branch to grow meant the entire grapevine would die. Her growth would be her downfall.

My grandfather noticed my childish stubbornness and assured me that this was for the whole grapevine. It’s better this way. Not wanting to cause trouble, I moved on and began to squeeze with all my might to cut this rebellious branch.

Snap!

Fluid began to pulse out of the old artery with an almost desperate will. I put away my scalpel and began to sheer away more of the fat deposits surrounding the heart. Years later, in the cold air of a cadaver lab, the grapevine had taken shape, manifesting itself into an aorta branching into its capillary beds. I dug a blunt tool underneath an artery, pulled it towards the surface, and deciphered its Latin name: External Carotid; Subclavian Artery. As I followed the arterial branches, I snapped the artery in two, suspended in air with no grapes to fall.

Once again, I viewed all the blood vessels as one connected system, and I understood. My cadaver died from a stroke, specifically from cancer that had both blocked the brain’s artery and redirected new arteries for itself. This was the sturdy branch who became greedy, stealing the energy from the main branch. Her growth became her downfall.

That night, I got a call from my family stating that my grandfather had passed. He had died in his sleep. We learned that “dying in your sleep” is most often because of a dysfunction of the heart, that, for some reason, simply ceases to pump.

You would think that his body might have learned from his years of pruning. That he would know which branches were to be cut and which were to be spared. You would think that I would have remembered to return his calls.

I wondered who would care for the grapevine now. How she could grow without her pruner? Would she meet the same fate as my cadaver?

Many years ago, I asked my grandfather, “what will happen when the grapevine dies?” He turned to his vineyard and reached out, picking off one of the green grapes. He showed it to me, “Even if this grapevine falls, its sweet grapes scatter out leaving sweet memories with everyone who eats it.”

He tossed the grape in the air and I caught it in my mouth. The taste of sweet memories.

Henri Levy, Class of 2024